Symbolism in Back to Anping Harbour

Table of Contents

Introduction #

Back to Anping Harbour (回來安平港) is a Taiwanese melodrama from 1972, which is regarded as the end of the “golden years” of Taiwanese language films (Ministry of Culture 2014). It was directed by Wu Fei-jian (吳飛劍) who worked on over twenty films throughout the 1960s and 1970s in Taiwan and its runtime is approximately 100 minutes (HKMDB 2020a; Taiwan Film Institute 2020a). The film prints were lost, but the Chinese Taipei Film Archive (CTFA) launched a project in 1989 which restored the film and a reconstructed version was released in 2014 (Ministry of Culture 2014; Rawnsley 2013, 1). The film tells the story of a mixed Taiwanese woman named Ah-Kim (阿金) from a relatively poor family, who faces discrimination due to her appearance and origin. She loses her parental figures (her mother and her grandfather) and regains a new family in the end. The plot shows parallels with the 1898 short story Madame Butterfly by John Luther Long. As it also features the elements of a Asian woman falling in love with a western foreigner who eventually abandons her.

The lead actress, Yang Li-Hua (楊麗花), plays two roles in the film: Hsiu-Chin (秀琴) a young woman from Anping and the grown-up Ah-Kim, who is Hsiu-Chin’s daughter. Other important characters in the film are the Dutch Naval Doctor Daley (達利) portrayed by Wai Wang (韋弘); Chih-Chiang (王志強), a medical student from Taipei and Ah-Kim’s love-interest who is played by Wei Shao-Peng (魏少朋); Man-Cheng (萬成伯), who is Hsiu-Chin’s father and Ah-Kims’s grandfather; Ah-Tsai (郭阿財) a street entertainer played by E Ah-Tsai (矮仔財) who helps Ah-Kim; and finally Mi-Ling (美玲) who is Chih-Chiang’s cousin and wants to marry him. She is played by Lan Chi (藍琪) and takes the role of an antagonist in the story.

Taiyupian as genre #

There are several types of Taiwanese language films, and according to the classification by Shih (2013) Back to Anping Harbour would fall in the category of Taiyupian (臺語片), not only because it is in Hokkien-language, but most importantly it was produced in Taiwan during the 1950s until 1980s. These movies were all produced by small privately owned companies, on a tight budget and in a short production cycle of a few weeks (Rawnsley 2013, 8). While the production quality of most Taiyupian was well below the cinematographic standard of the time, the genre was very popular in Taiwan (Rawnsley 2013, 9; Shih 2013, 242). Back to Anping Harbour as a late work of the era, provides an exception to the low-production quality. As it will be discussed below, the film demonstrates competent film making and does not suffer from typical quality issues such as “shaky background” (Rawnsley 2013, 6). The political situation in Taiwan under the role of the Kuomintang (KMT) made the production of non-Mandarin films difficult and the films were prone to be censored. This circumstance made the production of Taiyupian a risky investment as there was no guarantee that the movie would be screened in cinemas long enough to generate profit (Rawnsley 2013, 11). The tight budget of Back to Anping Harbour becomes evident in its simple black and white format, which is due to the lack of investment in equipment capable of producing a colour film. But the film can not only be classified by the production history, but also in terms of its contents. It is a melodrama featuring elements such as forbidden love, family issues, dramatic twists and also accidents (Ministry of Culture 2014).

Focus of Film Analysis #

This analysis focuses on imagery and symbolism in the film. While there are other elements that are more prominent perceivable to the audience such as the music, there subtle usage of certain props and location in combination with the camera work is a part of the movie that should not be dismissed easily. Throughout the movie several symbols are repeatedly placed in the frame. Most prominently a Christian style cross, which occurs the first time as a tombstone two minutes into the movie, foreshadowing Hsiu Chin’s death. The second symbol that occurs frequently are flowers of different types. These symbols are often carefully placed in prominent spots of the frame. Along with scene progression, they potentially unveil the director’s deeper intention in contextualizing the movie.

First there will be a detailed synopsis of the movie that also covers the setting. The synopsis will also feature simple characterizations of the main roles. Afterwards, there recurring symbols are identified alongside with a possible interpretation. This will take cultural contexts as well as scene composition into account as well. Even though music is an important element in the music, the scope of this essay would not do its importance justice. Therefore, the music will not be discussed in detail.

Detailed Synopsis #

The movie can be divided in three parts, which are constituted through the course of the story. The first part is the exposition which lasts around 36 minutes and tells the origin of Ah-Kim and her early childhood. The second part is 24 minutes long, establishes the main conflict, her love main interest and ends with her losing all her family. And the final part has a duration of 40 minutes and revolves around the conflict with her love interests family, her journey to become independent, her life in danger, and her eventual happy ending.

The film uses music as interludes, where many pieces are Taiwanese songs that were composed for the movie. Even though the music plays an important role in the overall composition and interpretation of the movie, it would go beyond the scope of this essay to review it in detail.

Setting #

The opening of the film prominently establishes the setting, which is in the small village Anping in southern Taiwan and also in the neighboring city of Tainan. The first minute of the film features two scenes. First, two fishermen talking on a boat which is at the coast of the river on a sunny day. Then, inside the home of Hsiu-Chin, which is a simple room with a limited set of furniture and overall a very rustic look. These two scenes quickly establish the setting of the everyday people and how they cope with the ups and downs of their lives.

The film features a mix of outdoor and indoor scenes, where the outdoor scenes all are filmed at real locations (as opposed to inside studio). The indoor set pieces of recurring locations might have been shot inside a studio, as the lighting is often too good for a regular house. However, there are some indoor scenes at locations that are only featured once, which could have been shot inside regular rooms. For example, Dr. Daly’s office in Anping appears like such a location.

The movie remains vague about the exact time period, but it begins sometime during the Japanese occupation period (1895 – 1945). Judging from the costumes, probably in the 1920s. The story has three jumps forward in time: once seven years, once fifteen years, and finally “several months”. This makes the story span across over 23 years and also beyond the Japanese occupation.

Part I #

The story starts with Hsiu-Chin being ill laying in her bed and being examined by Dr. Daly. He is temporarily in Taiwan and waiting for his ship to be repaired. His uniform somewhat resembles that of the Royal Dutch Navy, but the emblem on his peaked cap lacks the crown above the anchor. Nevertheless, the scene firmly establishes the most important characters for the first part of the movie and their position: Dr. Daly as willingly helping the locals in Anping, Hsiu-Chin as an damsel in distress type of character, and Man-Cheng who cares deeply about the well-being of his only daughter. The family friend hao, also delivers a line in the scene, but she is not of further importance in the story.

The dialogue at the end of the scene in conjunction with the next scene foreshadows Hsiu-Chin’s death. Daly says: “Uncle don’t worry. I’ll definitely cure her.” And immediately when he finishes the sentence there is a hard cut to the cemetery, where a cross shaped tomb stone is prominently in the right part of the frame and the sun is slanting on it.

The story proceeds and Daly cures Hsiu-Chin and her family invites him for a meal to showcase their gratitude and to celebrate a religious festival. She prepares a meal with fried fish. The film pays attention to detail, because in the background it is shown that the family holds a big pile of green vegetables. It is a typical custom to serve and hold a lot of green vegetables at home during East-Asian festivals, because it is a homophone with wealth and therefore would bring prosperity1. It should be noted here that this pile of vegetable only appears in this scene. During the meal, Daly somehow has difficulties eating with chopsticks, which is a stereotype of westerners. Especially given the fact that he is capable of speaking the local language, makes this stereotype quite strange. But it overall reinforces to the audience at that time, that Daly is a westerner, even though he is played by a Taiwanese actor. It also conveys that Daly is still not so familiar with the place. Hisu-Chin teaches Daly to use chop sticks and this also is the next small step in establishing their bond. The conversation at the table praises Daly’s skills as a doctor and western medicine.

Hsiu-Chin is also established as being “the prettiest girl in our village” through her local admirer Fu that her father wants her to get married to. But she developed stronger interest in Daly and visits him. She finds out that Daly had received a telegram stating that Daly’s father had died. She comforts Daly and this leads them to having a deeper emotional bond. They spend time with each other in his house and it is later revealed that she got pregnant from him. The first big conflict of the drama arises at this point, because Man-Cheng has to repay a debt to Fu’s father. He could marry his daughter to Fu and get out of the debt, however Hsiu-Chin does not want to marry Fu. She later reveals that she got pregnant from Daly and eventually (after some argument) Man-Cheng agrees to selling his fishing boat to pay off the debt and let Hsiu-Chin get married with Daly.

Right after Daly happily agrees to marry Hsiu-Chin he receives a letter from a Japanese soldier telling him that he has to leave Taiwan for good and immediately. This leads to the first major dramatic moment: the separation of Hsiu-Chin and Daly. He promises her to return and gives her a golden cross necklace as token for their love. And tells her to “pray to the harbor” if she feels sad.

The story then jumps seven years ahead, where little Ah-Kim is being bullied by other children for being a “bastard” and having “red hair”. This scene is the first time we get to meet Ah-Tsai, a street entertainer, who protects Ah-Kim from the other children. He is barely characterized, just briefly introduced as a friendly man. Most importantly, his clown costume makes him easily recognizable later. Ah-Kim returns home to her mother who is in ill in bed, and demands answers from her. Hsiu-Chin first tells her daughter that her father had gone to work and will come back soon. Some time later it rains outside, Hsiu-Chin’s condition gets worse and she tells Ah-Kim the truth of her origin and gives her the golden cross necklace. Man-Cheng also returns home late on that rainy day, and Hisu-Chin dies in that night. On the nightstand is a candle that flickers and extinguishes in the moment when the mother deceases. First the candle is not in focus, but when the wind blows it out the focus is shifted to it.

Part II #

Starting from the second third of the film, the setting jumps forward in time right past World War II, which is revealed through a conversation of Man-Cheng with a fellow fisherman. Both men are sitting at the river fishing and talking. We get to meet the grown-up Ah-Kim who looks exactly like her mother, except that she has “red hair and cloudy eyes”. She walks into the scene and after a small conversation, Man-Cheng accidentally falls into the water. This is also how Chih-Chiang and his girlfriend / cousin Mi-Ling are introduced: they happen to be strolling at the riverside as well and Chih-Chiang hears Ah-Kim calling for help. Chih-Chiang jumps into the water and saves Man-Cheng. They return to Ah-Kims home together, and Mi-Ling disapproves of the situation and senses that Chih-Chiang and Ah-Kim are getting interested in each other. Chih-Chiang prepares hot ginger tea for the grandfather. This scene together with the previous one points towards that Daly and Chih-Chiang are similar in their nature: both value helping others in need. However, Daly has not done such a “heroic” deed like the young Chih-Chiang did. Another key in this scene is that it begins from Mi-Lings perspective. The camera is right behind her, she looks at the grandfather on the right side, and when she turns left to look at Chih-Chiang and Ah-Kim, the camera also pans in the same direction. When Ah-Kim takes the cup of tea to her grandfather, Chih-Chiang’s eyes follow her. This is when Mi-Ling starts a minor argument with Chih-Chiang that he should not mind other people’s business. While the camerawork establish Mi-Ling as being jealous and possessive, the dialogue reveals that Chih-Chiang has no deep interest in a relationship with her. After Mi-Ling decides to leave the house without him, Ah-Kim and her grandfather say goodbye to him. They exchange some courtesies and Ah-Kim’s facial expression and hand gesture establish that she has fallen for Chih-Chiang.

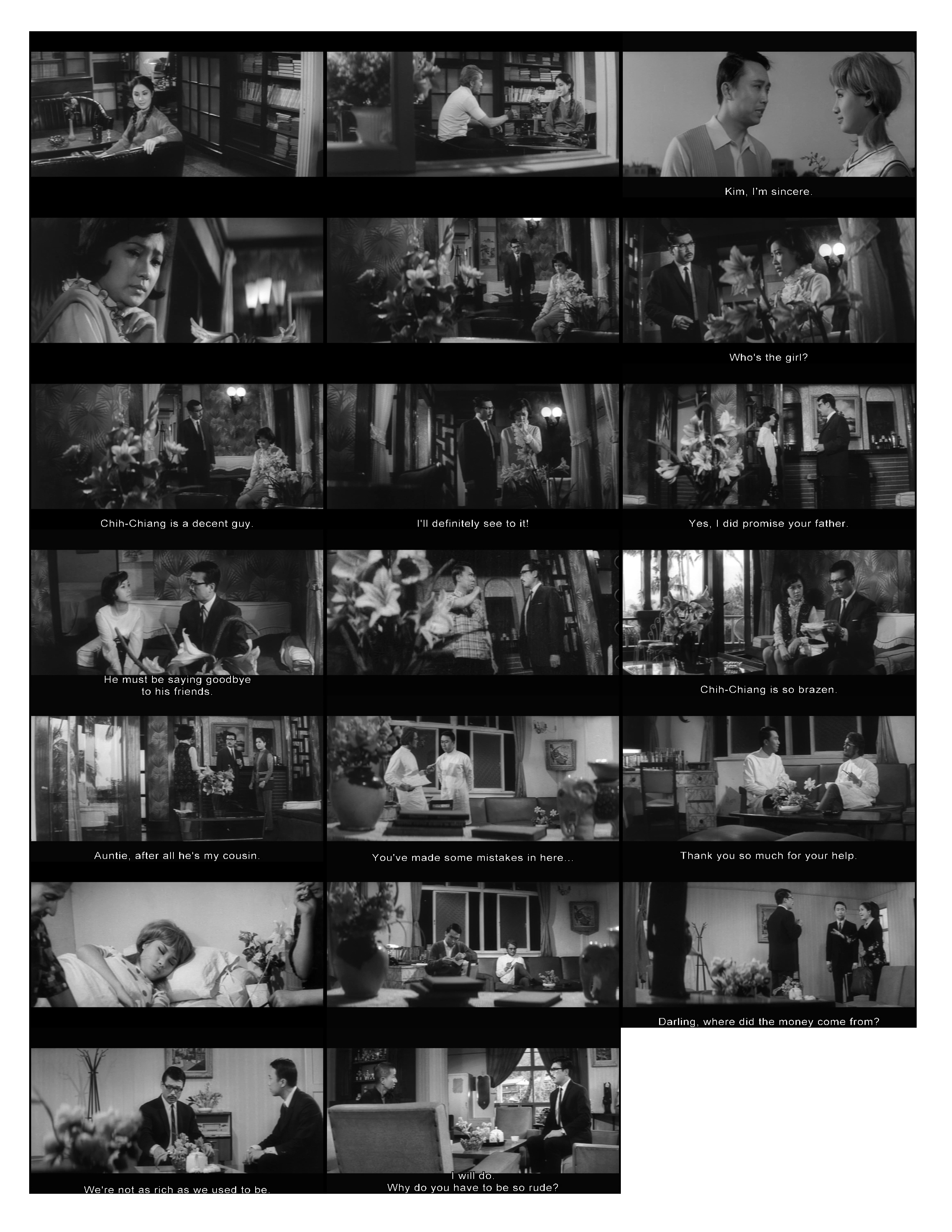

Later Mi-Ling talks to Chih-Chiang’s father about the growing romance and the father disapproves of this as well. Mi-Ling emerges as a kind of rival or antagonist in relation to Ah-Kim. As we shall see, Mi-Ling intervenes and influences events several times throughout the story. This conversation also provides a first glance into Chih-Chiang’s home, which is very well decorated, has expensive furniture and overall showcases the wealth of his family. There are Formosa Lilies2 on the table as decoration, the first time we encounter this prop prominently placed in the frame. The father also is established of having strong traditional views and to pursue materialistic goals. Meanwhile, Chih-Chiang and Ah-Kim stroll through Anping and there are quite a few outdoor scenes featuring the famous buildings and sites of the town. At the riverside Ah-Kim tells Chih-Chiang about her origin and they develop a deeper emotional bond. When Chih-Chiang asks about her father, she holds the golden cross necklace in her hands.

This sequence starting from Chih-Chiang rescuing Man-Cheng and ending with Ah-Kim and her new love looking at the sky, demonstrates that the film uses certain stylistic devices rather competently. Chih-Chiang gets a characterization through his heroic actions and the things he says as well people talking about him being a “decent guy”. This paints a positive impression of him. Mi-Ling on the other hand receives a negative characterization that is created through carefully executed camerawork as well as her facial expressions. Ah-Kim is mainly described through her looks and her origins in this sequence. Almost as if these two things are the only qualities that define her. Arguably, it also draws a picture of the main character that does not take much influence in the story surrounding her. Things happen to her and she asks others for help. The sequence also establishes the foundation for the upcoming conflicts by showcasing the poverty of Ah-Kim and her grandfather, the wealthy background of Chih-Chiang’s family, Mi-Ling’s interference in the love affair, and also foreshadowing Man-Cheng’s death.

After some undefined time later, Ah-Kim and Chih-Chiang go strolling by the riverside again and talk about being “friends forever”. But Ah-Kim is well aware of her social status and being a “poor match” for Chih-Chiang who is from a rich family. This is where the second major conflict emerges: Chih-Chiang wants to marry Ah-Kim, but there are several obstacles. First, he is about to go abroad to study medicine. Secondly, Ah-Kim’s grandfather disapproves of the poor match. And finally, Chih-Chiang’s father also does not agree that his son would marry “a women of red hair and cloudy eyes”. The first two obstacles are overcome quickly, through a discussion between Man-Cheng, Ah-Kim and Chih-Chiang. The young couple manages to convince the grandfather to agree and Chih-Chiang promises to marry Ah-Kim two years later after he returns from abroad. However, the conflict with his father remains unresolved.

Ah-Kim goes to visit her mothers grave, which is a cross shaped tombstone on the highest point of the local cemetery. She prays and holds the golden cross necklace in her hands. Suddenly, Chih-Chiang appears and promises her that he would marry her, even if his family disapproves. They make their farewell and Chih-Chiang leaves in a propeller aircraft. When Ah-Kim sadly returns home, she finds her grandfather collapsed on the floor. She wakes him up and he tells her to find her lost uncle Lou, because he knows that he will not have much time left to live. The dialogue ends with Man-Cheng dead and Ah-Kim crying. The shot confirming his death is from above, a new camera angle that was not used before, and also twisted by a 45-degree angle supplementing the unsettling nature of the tragic event. This is exactly at the end of the second third of the film and Ah-Kim has reached her lowest point in the story. She is all alone and has no family left. She goes to her mother’s grave again and also to the riverside and prays holding the golden cross necklace.

Part III #

Ah-Kim leaves Anping and she tries to find her lost uncle in another nearby city. She has no luck at first, but by chance bumps into Ah-Tsai, who recognizes her. He takes her as his god-daughter and they go to the inn where Ah-Tsai is staying. The first shot which introduces the owner of the inn shows him cleaning the floor. It is a close-up shot of his face reflected in the water bucket. This shot hints at his true identity coming from a place close to the water. It turns out that the owner of the inn is the lost uncle Lou that Man-Cheng mentioned before he died. When Lou learns about the news that his father had died, he immediately starts crying, but as an overall result Ah-Kim has partially regained some of her family.

Meanwhile, Chih-Chiang’s family receives letters from him address to Ah-Kim, and we also learn that his father’s business is not doing well and that they would lose their fortune. Mi-Ling takes the letters and throws them into the river. Then the scene cuts to Chih-Chiang studying abroad, a narrator explains that several months have passed and it is revealed that his professor is Daly. Instead of a uniform Daly is now wearing a lab coat and he also is smoking a pipe, which conveys how he has aged and does not fit the role of a lover anymore. There are Formosa Lilies on the table and Daly asks his student what was bothering him as he made mistakes in his thesis and also was “restless” these days. Chih-Chiang states that he was alright. The next cut shows a traditional Taiwanese building roof. The connection of these two elements (the dialogue and the cut) reveal how much Chih-Chiang misses his home.

In the following scene, it is shown how Ah-Kim and Ah-Tsai make their living as street entertainers and that they are both appear to be successful together. After their performance, they meet Mi-Ling driving by in a car. She tells them that Chih-Chiang’s father has financial problems. Later back in the inn, Ah-Kim decides to use her fortune to help Chih-Chiang’s family. Ah-Kim and Ah-Tsai come up with a scheme to give the money to the family without them losing their face. Ah-Tsai in disguise gives the money to Chih-Chiang’s father, who is at rock-bottom, drinking beer in a simple home, similar to Man-Cheng’s. Ah-Tsai tells him that Chih-Chiang received a scholarship and the money is left from that. Arguably, this is the first and only time Ah-Kim has an active influence others and the outcome of the story. She makes a decision and has the means to carry it out. This shows that she has undergone a transformation from being constantly in need of aid from others to gaining true agency.

More time passes, and Ah-Kim is at the market with Ah-Tsai. She is suddenly hit by a car and it is revealed that it is Mi-Ling’s. They take Ah-Kim to the hospital and Mi-Ling has strong remorse for what has happened to Ah-Kim and how she resented her before. Therefore, she sends a telegram to Chih-Chiang, hoping that he would come back to Anping and help to cure Ah-Kim. When he receives the telegram he convinces Daly to return together with him. They return in a jet plane and consult with the local doctor. When Daly and Chih-Chiang go to see Ah-Kim in the hospital, Daly immediately notices Ah-Kim’s striking resemblance of Hsiu-Chin. This realization is supported with a super zoom on her face following a super zoom on his. He remains calm and he states that her life is not in danger, but she is still unconscious.

Chin-Chiang meets his family and he convinces his father that he should be allowed to marry Ah-Kim, but his father insists that he should marry Mi-Ling. He goes to see Ah-Kim in the hospital, where she woke up in the mean time. They discuss the problem with Ah-Tsai who then decides to talk to Chih-Chiang’s father. Ah-Tsai reveals to the father, that the money was from Ah-Kim all along and only after hearing this fact, he changes his mind and lets them get married.

The final scene is set outdoors at the cemetery, where Daly is at Hsiu-Chin’s grave and Ah-Kim and her fiancée are strolling up the hill. There is a short shot showing Mi-Ling watching them from afar, the camera zooms in to her face and she sadly looks down, representing that she gave up what she fought for throughout the story. Daly is talking to the grave and expressing his regrets for not coming back earlier and promising to help the daughter he never met. Ah-Kim hears it and walks up to him, he asked whether she is his daughter and she immediately embraces Daly as her father. And the movie ends with the camera panning to the sky.

After first regaining her family through Ah-Tsai and Lou, Ah-Kim’s family becomes somewhat complete through being engaged with Chih-Chiang and finding her father. However, she does not get a mother back.

Symbolism #

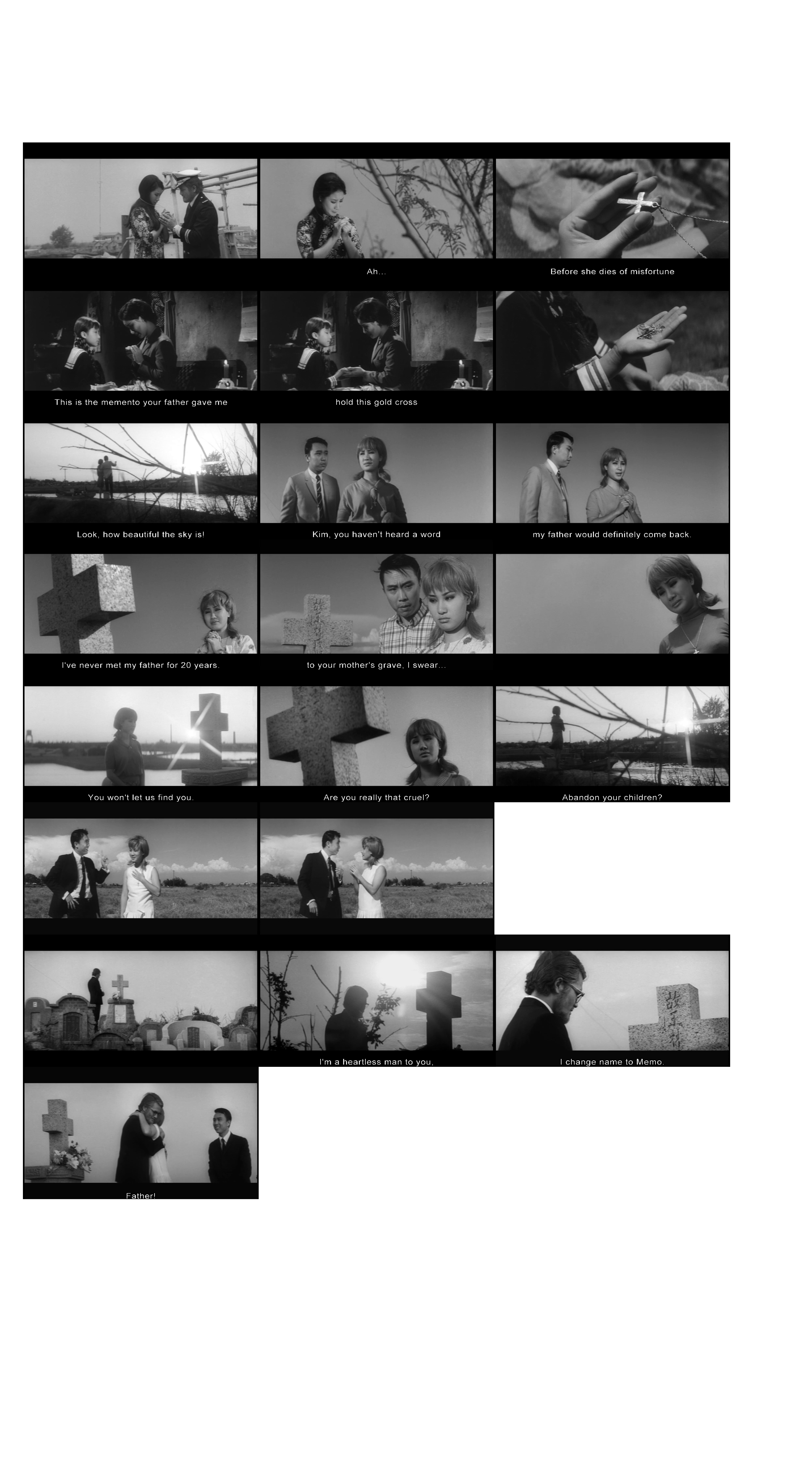

The Cross #

The cross appears throughout the film in at least three forms, most obviously as the golden necklace and the tombstone. But also the lens flare of the sun in certain scenes resemble the shape of a cross. The symbol appears in at least eight scenes in any of the aforementioned forms, sometimes even simultaneously. The necklace is the most frequent one, which is also mentioned most often. It is also quite often visible, however, usually it is very small in the frame, appears for a few seconds. Ah-Kim only touches it in certain situations, bringing it to the viewers attention. The tomb stone and the lens flare shot of the sun are not as often which makes them even more eye catching. All scenes that feature or mention either of these elements are collected in the figure below.

All scenes have in common that they represent a major turn in Ah-Kim’s life (considering that she is in the womb of Hsiu-Chin):

- The first shot of the credits at the beginning of the movie

- Daly gives Hsiu-Chin the necklace and leaves Anping

- The first time Ah-Kim asks her mother about her father

- Before Hsiuh-Chin dies and gives the necklace to her daughter

- Ah-Kim is an adult and goes out with Chih-Chiang

- Chih-Chiang is about to leave Anping and promises Ah-Kim that he would return

- After Man-Cheng dies

- Daly finally returns to Hsiu-Chin’s grave

At the first glance the cross is a strong reminder of Christianity. Especially, the tomb stone which is prominently placed on top of the hill at the cemetary. Not only its placement, but even more the fact that it is the only cross-shaped tomb stone between others that have a traditional Asian style. As mentioned above, the tomb stone is used at the very beginning of the movie to foreshadow Hsiu-Chin’s fate. The start of the music with a “bang” at the beginning of the credit scene underlines this idea. Also, the golden necklace strongly resembles a Christian style cross. It is a rather uncommon token in the movie, as other characters barely wear any jewelry. The initial thought that Ah-Kim’s family just follows the Christian religion is hard to defend, as it would not be compatible with them celebrating a traditional Chinese festival. Additionally, the idea to pray to the harbour is in disagreement with Christian traditions.

Nevertheless, the cross arguably does have a connection to Christianity, but in a more metaphorical and historical manner. It should be noted that the Taiwanese viewers at the time where familiar with Christians. Not only were high ranking members of the Kuomintang Christians, but also the Presbyterian missionaries arrived in Taiwan as early as 1865 (Rubinstein 2003, 207). They were also the first Westerners who systematically studied the Minnan / Hokkien dialects and developed romanized dictionaries (Rubinstein 2003, 207). They also had a reputation of taking care of ill people and established western style health care facilities quite early on the island (Rubinstein 2003, 208). This would fit Daly quite well, as he is able to speak the local language and is a doctor. However, he is also Dutch and a member of the navy, but the Presbyterians were civilians from Great Britain, Canada and the United States (Rubinstein 2003, 206). But it could be argued that for the average Taiwanese viewers these details did not really matter. But it rather mattered that the Westerners were perceived as competent doctors and christians were people who were willingly helping the local population. These ideas are all condensed in the cross necklace that directly stems from Daly.

In a spiritual and metaphorical sense, the cross in combination with the prayer is relatively obscure. The necklace is also an artifact that represents hope and provides comfort in the times of crisis. Arguably, even Ah-Kim does not fully understand the meaning of praying to the harbor, but it helps her to cope with difficult situations. The psychological relief of her grievances and her longing for a father (and later in the story for a family) come together in the simple ritual of standing at the waterfront and pray.

The lens flare shots of the sun arguably represent Hsiu-Chin watching over her daughter, as the first time it appears is after she dies. Chih-Chiang pointing at the sky and praising its beauty, as Hsiu-Chin was praised before. There are also two-shots that combine the sun with the tomb stone, while the characters refer to the Hsiu-Chin. These shots establish a strong connection between these elements. Therefore, the cross points at the Western culture, and at hope, but also at bittersweet memories.

Flowers #

It can easily be argued that flowers are just a common prop in any film production. Not only are flowers a common item for indoor decoration in real households, but also add richness to the frame composition. However, given the prominence of specific flowers throughout the film and also the metaphorical mentioning of flowers in Madame Butterfly, it is a fine detail that should not be easily dismissed. Not only the presence of flowers matter, but as we shall see their absence is of importance as well.

The most frequent type of flower is the formosa lily, which is also native to Taiwan. It appears in the house of Chih-Chiang’s family, but also in the hospital and Chih-Chiang’s study room. Especially, Chih-Chiang’s father is often in a scene together with formosa lilies. Other flowers are less frequent, such as roses in Daly’s house in Anping, or hand picked flowers in other locations.

The formosa lily has quite a few different meanings in Taiwanese culture, including values such as purity, grace and resilience (Lin 2017, 109; Taiwan Info 2003). But it also stands for the island of Taiwan itself and a shared cultural memory (Lin 2017, 104). In the film the lilies represent the traditional Taiwanese values and the implied social hierarchy that comes with it. Chih-Chiang’s family is wealthy and follow the traditional Taiwanese way of life and they have formosa lilies in every room and every scene. Ah-Kim’s house does not have any lilies, they do not have flowers at all. Besides indicating their financial situation, it also supplements that Man-Cheng is more flexible when it comes to traditions that involve the social status. Chih-Chiang’s father only does not have formosa lilies in two scenes: the first one where he becomes bankrupt and just cannot afford them anymore. But right after he regains his fortune, the lilies are back on the living room table. Especially, in the scene where Chih-Chiang returns from his study abroad and has his last argument with his father, there are the lilies again on the table. However, when Ah-Tsai reveals in the very end that Ah-Kim saved the family from poverty, there are no lilies on the table. This symbolizes how Chih-Chiang’s father also starts becoming more flexible in his views.

There are also two scenes that are set in Chih-Chiang’s study room. The first scene, Chih-Chiang does not tell Daly that he misses home, but there are formosa lilies on the couch table that represent his true feelings. In second scene in the same room the lilies are gone and different flowers have taken their place. Also, when Ah-Kim is hospitalized there are formosa lilies on her night stand. Arguably, the flowers are showing that Ah-Kim has the true Taiwanese values inside her all along.

Conclusions #

At first glance Back to Anping Harbour is a shallow film that was produced for pure entertainment. It is true, that it is an entertaining drama that has nice songs that a large audience would enjoy. However, the film does make clever use of simple stylistic elements to enhance its meaning and to add more depth to the story. It is evident that the film was at the pinnacle of Taiyupian, as the film makers have consolidated their cinematographic skills and used them to create a competent movie. Even though the film features typical tropes, it adds layers of ambiguity to them, which make them less black and white than the screen makes them appear. Sadly, the movie falls a bit short in terms of giving Ah-Kim agency. She is rarely in charge of her own destiny, but this also makes the film more worth wile to watch, as it is an authentic product of its time.

References #

-

Borstnar, Nils, Eckhard Pabst, and Hans Jürgen Wulff. 2008. Einführung in Die Film- Und Fernsehwissenschaft. 2., überarb. Aufl. UTB Medienwissenschaft, Filmwissenschaft 2362. Konstanz: UVK Verl.-Ges.

-

Clart, Philip, and Charles Brewer Jones, eds. 2003. Religion in Modern Taiwan: Tradition and Innovation in a Changing Society. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

-

Filmosa. 2019. “Back to Anping Harbour.” June 2, 2019. https://ilhafilmosa.com/back-to-anping-harbour/.

-

HKMDB. 2020a. “吳飛劍 Wu Fei-Chien.” 2020. http://hkmdb.com/db/people/view.mhtml?id=16803&display_set=big5.

-

———. 2020b. “回來安平港 (1970).” 2020. http://hkmdb.com/db/movies/view.mhtml?id=14859&display_set=big5.

-

Hong, Gou-Juin. 2011. Taiwan Cinema: A Contested Nation on Screen. New York, NY [u.a.: Palgrave Macmillan. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/9780230118324.

-

Kenworthy, Christopher. 2012. Master Shots: 100 Advanced Camera Techniques to Get an Expensive Look on Your Low-Budget Movie. 2nd ed. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions.

-

Laliberté, André. 2003. “Mainstream Buddhist Organizations and the Kuomintang, 1947–1996.” In Religion in Modern Taiwan: Tradition and Innovation in a Changing Society, 158–85. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

-

Lin, Su-Chi. 2017. “Intercultural Mediation: A Visual Cultural Study of Art and Missionin Contemporary Taiwan.” PhD thesis, Graduate Theological Union.

-

Lin, Sylvia Li-chun. 2007. Representing Atrocity in Taiwan: The 2/28 Incident and White Terror in Fiction and Film. Global Chinese Culture. New York: Columbia University Press.

-

Long, John Luther. 1904. Madame Butterfly. The Century Co.

-

Mascelli, Joseph V. 1998. The Five c’s of Cinematography: Motion Picture Filming Techniques. 1st Silman-James Press ed. Los Angeles: Silman-James Press.

-

Ministry of Culture. 2014. “Back to Anping Harbor. Taiwan Culture Toolkit.” March 5, 2014. https://toolkit.culture.tw/en/filminfo_62_308.html.

-

Rawnsley, Ming-Yeh T. 2013. “Taiwanese-Language Cinema: State Versus Market, National Versus Transnational.” Oriental Archive 81 (3): 1–22.

-

Rubinstein, Murray A. 2003. “The Presbyterian Church and the Struggle for Minnan/Hakka Selfhood in the Republic of China.” In Religion in Modern Taiwan: Tradition and Innovation in a Changing Society, 186–256. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

-

Shih, Evelyn. 2013. “Getting the Last Laugh: Opera Legacy, Comedy and Camp as Attraction in the Late Years of Taiyupian.” Journal of Chinese Cinemas 7 (3): 241–62. https://doi.org/10.1386/jcc.7.3.241_1.

-

Su, Wendy. 2014. “Cultural Policy and Film Industry as Negotiation of Power: The Chinese State’s Role and Strategies in Its Engagement with Global Hollywood 1994–2012.” Pacific Affairs 87 (1): 93–114. https://doi.org/10.5509/201487193.

-

Taiwan Film Institute. 2020a. “吳飛劍 Wu Fei Chien. 財團法人國家電影中心 / 台灣電影數位典藏中心 Chinese Taipei Film Archive / Center for Taiwan Film Digital Movie Archives.” 2020. http://www.ctfa.org.tw/filmmaker/content.php?id=560.

-

———. 2020b. “回來安平港《數位修復珍藏版》DVD.” 2020. https://www.tfi.org.tw/Publication/PublicationsInfo?PublicationId=312.

-

e"> ———. 2020c. “臺灣電影數位修復計劃-計畫簡介.” 2020. https://tcdrp.tfi.org.tw/achieve.asp?Y_NO=3&M_ID=9.

-

Taiwan Info. 2003. “Botanists’ Labor of Love Revives Formosan Lily Population.” December 26, 2003. http://web.archive.org/web/20140222002913/http://taiwaninfo.nat.gov.tw/fp.asp?xItem=20431&CtNode=103.

-

Wang, Chun-chi. 2012. “Affinity and Difference Between Japanese Cinema and Taiyu Pian Through a Comparative Study of Japanese and Taiyu Pian Melodramas.” Wenshan Review of Literature and Culture 6 (1): 72–102. https://www.wreview.org/index.php/archive/38-vol-6-no-1/108-affinity-and-difference-between-japanese-cinema-and-taiyu-pian-through-a-comparative-study-of-japanese-and-taiyu-pian-melodramas.html.

-

Wicks, James. 2014. Transnational Representations: The State of Taiwan Film in the 1960s and 1970s. Hong Kong: HKU Press.

-

Yeh, Yueh-yu, and Darrell Davis. 2012. Taiwan Film Directors: A Treasure Island.

-

Zhang, Yingjin. 2013. “Articulating Sadness, Gendering Space: The Politics and Poetics of Taiyu Films from 1960s Taiwan.” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 25 (1): 1–46. www.jstor.org/stable/42940461.

-

“回來安平港.” 2020. In Wikipedia (Chinese). https://zh.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=%E5%9B%9E%E4%BE%86%E5%AE%89%E5%B9%B3%E6%B8%AF&oldid=57848665.